Critical Thinking for Children with Developmental Disorders

While it is widely recognised that critical thinking skills are extremely important, a lot of therapists, teachers and parents feel that defining and teaching these skills to young children, particularly children with pervasive developmental disorders (PDD), remains an elusive task. Nevertheless, there is increasing evidence to suggest that critical thinking can be taught and that instruction should start as early as possible. Drawing on the vast range of definitions and techniques available for teaching critical thinking skills, we have developed a 3-cycle strategy that can be easily and flexibly used to address the particular needs of pre-school and primary school children with developmental disorders.

The strategy is based on the premise that this group of children can particularly benefit from a structured, interactive and motivational approach that reflects the children’s interests.

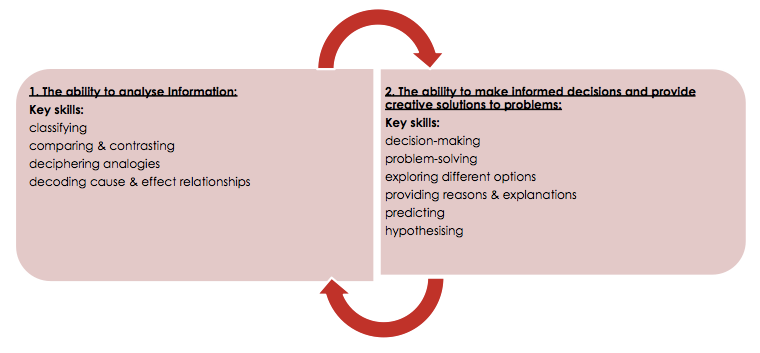

Critical Thinking - A definition in the context of our 3-cycle strategy:

Critical Thinking is:

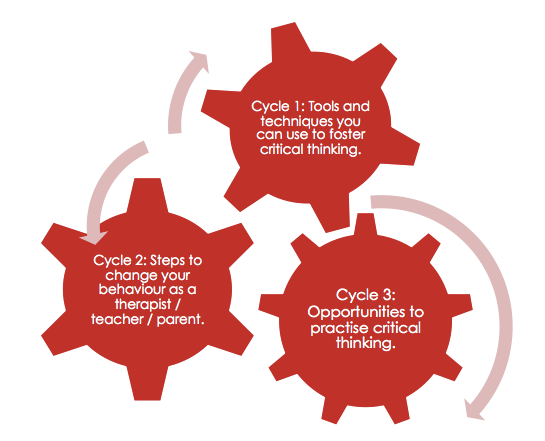

Our 3-cycle strategy:

Our strategy consists of 3 cycles that are inextricably linked:

Cycle 1: Tools and techniques you can use to foster critical thinking.

Cycle 2: Steps to change your behaviour as a therapist / teacher / parent, in order to encourage critical thinking.

Cycle 3: Opportunities you can use to practise critical thinking.

Cycle 1: Tools and techniques you can use

1) Make use of Thinking Routines.

Thinking Routines is a concept which was originally developed in the context of the Visible Thinking Project by the Harvard School of Education (Project Zero). Thinking Routines are sets of steps and questions that can be flexibly used on a regular basis to strengthen different thinking skills. Particularly regarding children with PDD, they could not only be helpful in enhancing their thinking skills but also in fulfilling their pronounced need for structure and routine. Here is an example of a simple thinking routine:

Name of Thinking Routine: “See – Think – Wonder”

Skills targeted: Making justified interpretations and thinking creatively.

How to use this routine: Ask your child to observe an object that is of interest to them. It could be a work of art or any other object you may encounter during an outdoor activity. Then, ask your child the following three questions:

What do you see? => “I see…”

What do you think about that? => “I think…”

What does it make you wonder? => “I wonder…”

Always prompt the child to support every answer with a reason. Practising this thinking routine in similar contexts on a regular basis can help your child to become more confident in using this thinking pattern independently.

For more information on other thinking routines, such as the Explanation Game, the Option Explosion thinking routine etc., we recommend that you visit the website of the Visible Thinking Project developed by the Harvard School of Education: http://www.visiblethinkingpz.org

2) Ask open-ended questions.

Asking your child skilled questions that involve higher-order thinking processes is crucial. Ideally, you should opt for questions that prompt children to infer an answer from clues, draw on their personal experiences and creativity or explore multiple options when making a decision. Examples*:

- What makes your say that?

- What would change if…?

- Are there any other options (before we make a decision)?

*Please note that one of our upcoming blog posts will be dealing specifically with the subject of Asking Questions.

3) Equip your child with a simple problem-solving strategy.

Problem-solving is a key component of critical thinking. If you can teach your children a simple sequence of steps they can follow to solve a problem, you are sure to enhance their ability to think independently. In a study published by the Remedial and Special Education journal, entitled “Increasing the Problem-Solving Skills of Students with Developmental Disabilities”, the research team has employed the 3-phase problem-solving strategy set out below:

Phase 1: “Set a goal”=> Encourage your child to ask and answer the question: “What is the problem?” and then set a goal for solving it.

Phase 2: “Take action” => Encourage your child to ask and answer the question: “What can I do to solve the problem?” and then develop an action plan.

Phase 3: “Adjust goal or plan.” => Encourage your child to evaluate the results of the initial action plan by asking the question “Did that solve the problem?” and then adapt the said action plan, if needed.

4) Use specialised resources: although you can always come up with your own activities, as a busy therapist, teacher or parent, you don’t always have to reinvent the wheel. Enrich your library with specialised resources to offer your child ample and regular critical thinking practice.

Cycle 2: Steps to change your behaviour as a therapist / teacher / parent

Being aware of the best tools is one thing, but no tool will be effective unless you adopt a more “critical-thinking-friendly” attitude towards your child:

1) Be patient: when discussing any problem with your child, don’t “feed” them the answers. Give them time to think! Remember: to help children think you need to let them think!

2) Embrace your child’s questions. Encourage your child to ask questions and justify your answers to them.

3) Model critical thinking. Provide reasons when you describe or explain something to your child and let your child see what process you follow to solve day-to-day problems.

4) Let your child make mistakes. Mistakes are a valuable opportunity to learn and explore different options for solving a problem.

Cycle 3: Opportunities you can use to foster critical thinking

Almost any instance in your child’s life offers an opportunity to practice critical thinking, as long as you remember that critical thinking instruction should always be fun and never be imposed on the child. We have selected 4 useful contexts for critical thinking practice:

1) Your child’s hobbies and talents: build on your child’s interests and make use of thinking routines and skilled questions while talking about things that your child loves doing.

2) Children’s literature: read books together and use appropriate questions to promote a deep understanding of the stories you read, while targeting a variety of critical thinking skills.

3) Homework time: refrain from “feeding” your child the answers. Doing this will be more valuable in the long run than achieving a good grade in a homework assignment.

4) Talking through a problem together: this could be any kind of problem, at home or at school. Guide your child in using the 3-step problem-solving strategy outlined above.

Critical thinking takes a lot of patience and perseverance, but it is one of the most valuable life skills you can foster.

Sofia Natsa

Author Upbility.net

Sources used:

- http://www.beachcenter.org

- http://www.hanen.org

- http://www.thinkingclassroom.co.uk

- http://www.brighthorizons.com

- https://dyslexia.wordpress.com

- http://www.parentingscience.com/teaching-critical-thinking.html

- http://www.parentingscience.com/teaching-critical-thinking.html

- http://oupeltglobalblog.com/2013/10/09/five-easy-ways-in-which-you-can-encourage-young-children-to-think-critically/

- http://oupeltglobalblog.com/2013/10/09/five-easy-ways-in-which-you-can-encourage-young-children-to-think-critically/

- http://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/teaching-professor-blog/teaching-critical-thinking-are-we-clear/

Suggested articles for parents:

- 10 Ways to Teach Your Child the Skills to Prevent Sexual Abuse

- Building Social Skills in Young Children!

More Articles on Upbility.net

Free Poster Download "Stop Telling Children To Be Careful"

Suggested e Books on child Psychology

Social Skills e book: